Being appointed as a member of the Governing Board of an association such as EASL attests to a certain level of achievement in your career, with all this entails in effort and commitment. For women in hepatology, such an appointment often takes on a more important dimension. That of being a role model, breaking down traditional barriers (barriers that are so steeped in history, they out may outlast male colleagues), and that open up new horizons for the coming generation of hepatologists.

Find out below the opinions of some of the brilliant women hepatologists, past and present, who have served on the EASL Governing Board. They have paved the way to more recognition – not only of their invaluable contribution to hepatology, but also of the difficulties they have faced as women. From the first woman ever nominated in 1993, Prof. Maggie Bassendine, to the most recent in 2020, Prof. Saskia van Mil, discover how different generations perceive the challenges ahead, to us achieving gender equality in science.

Quick access menu

Prof. Maggie Bassendine

First female member of the EASL Scientific Committee (1993–1996)

Emeritus Professor of Hepatology

Translational and Clinical Research Institute, The Medical School, Newcastle University, UK

The World Health Organization has analysed the gender ‘issue’ in global health and concluded that it is ‘delivered by women, led by men’. This means that parity between men and women is still a ‘work in progress’. We must, however, acknowledge that progress has been and continues to be made, albeit too slowly.

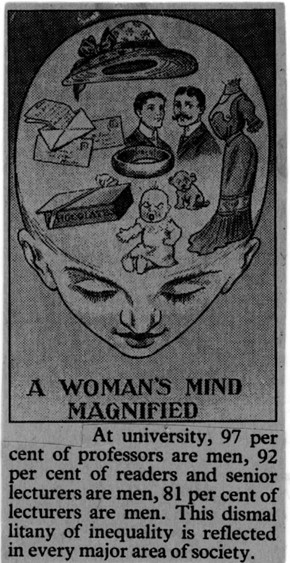

When I was a medical student in London in the late 1960s, I cut out an illustration of ‘A women’s mind magnified’ (Figure) taken from the time of the suffragettes, with the contemporaneous ‘60s text: ‘At university 97 per cent of professors are men, 92 per cent of readers and senior lecturers (associate professors) are men and 81 per cent of lecturers are men. This dismal litany of inequality is reflected in every major area of society.’

Five decades later, the percentage of clinical professors on university contracts who were women in the UK had risen to just 13%, despite nearly half of all doctors being women (1).

Most men and women aspire to the same things – a happy home/family life and an interesting, rewarding job. Sheila Sherlock, a founding member of EASL, and my mother, an inspiring teacher, both achieved this. However, all too often, it is still the case that women in leadership positions are unmarried or have just one child. After I became the first woman on the EASL Governing Board in the 1990s, I had a high enough profile to be the subject of ‘lifeline’ in the Lancet. My reply to the question ‘what is your unrealised ambition’ was ‘to combine hospital medicine with having a family’ (2). The reason this remains more difficult for women than men is because of gender-related biological differences (their reproductive role and it’s timing in relation to medical and specialist training) together with socio-economic and cultural factors, including their role as carers at the beginning (children) and end (parents) of their career. Many other factors including gender stereotyping influence career options (3).

Societal change can be achieved in two ways:

- Through a series of small steps made by individuals. Many individual ‘Women in Hepatology’ have made these steps and this was celebrated in 2010 when 60 of us came together in Sienna Italy, at a meeting organised by Professor Erica Villa (4), to bring their personal and gender orientated views to the field of Hepatology. Individual ‘Men in Hepatology’ have also moved forwards and recognised that doing the same thing over and over again will not lead to change – I thank them. Regrettably, the behaviour of others still reinforces traditional hierarchical male medical structures. Individuals, whatever their gender, need to appreciate and respect each other.

- Through institutions such as EASL, who have committed in a recent policy statement to ‘continue to work towards parity in order to achieve excellence in research, clinical practice and education within the arena of hepatology.’

Since I qualified as a doctor 50 years ago, there has been an extraordinary explosion in the biological sciences, which is now filtering through to improvements in patient care. There has never been a more exciting time to work in the field of hepatology, whether as a clinician and/or scientist. Both men and women want to contribute to this endeavour and need to continue to work together in their workplaces and professional associations (5) such as EASL to provide an environment where all individuals can not only flourish, but also achieve a good work–life balance.

References

- Boylan J, Dacre J, Gordon H. Addressing women’s under-representation in medical leadership. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):e14.

- Lifeline: Maggie Bassendine. The Lancet 1997;349,1562

- Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, Kolehmainen C. Why is John More Likely to Become Department Chair Than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:197-214.

- Villa E, Vukotic R, Camma C, Petta S, Di Leo A, Gitto S, et al. Reproductive status is associated with the severity of fibrosis in women with hepatitis C. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44624.

- Gender equality in medicine; change is coming. Editorial, The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2019; 4, 893

Most men and women aspire to the same things – a happy home/family life and an interesting, rewarding job. Sheila Sherlock, a founding member of EASL, and my mother, an inspiring teacher, achieved both.

All too often, it is still the case that women in leadership positions are unmarried or have just one child.

Both men and women need to continue to work together in their workplaces and professional associations, such as EASL, to provide an environment where all individuals can not only flourish, but also achieve a good work–life balance.

Prof. Patrizia Burra, MD, PhD

EASL EU Policy Councilor (2012–2016)

Head of Multivisceral Transplant Unit-Gastroenterology, Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology

Padova University Hospital, Italy

Almost in all the countries, women are still underrepresented – in academic leadership positions, journal authorship, and speaker invitations.

It is very important that the problem of gender inequality in medicine be brought to the attention of the public opinion, talk about it in the media, raise awareness among students and future doctors.

I firmly believe that eliminating gender bias can be achieved through a series of small steps made by individuals and institutions.

As a Medical Doctor for over 35 years, I have spent my entire professional career in gastroenterology and hepatology.

Since joining in 1995, I have maintained a very good and active relationship with EASL. In 2003, I was the organiser of the EASL Monothematic Conference “Strategies for liver support: from stem cells to Xenotransplantation” held in Venice (Italy). After that, I was EASL EU Spokesperson in 2010 and EASL EU Policy Councillor between 2012 and 2016. Moreover, I have been Co-chair with Tom Karlsen and Michael Manns of “The Lancet – EASL Commission on liver diseases in Europe” since 2018. I also contributed to the publication of the ESPGHAN (European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition) and the EASL position paper on the health care transition of youth with liver disease into the adult health system, in 2018. Currently, I am Deputy Editor of the Journal of Hepatology.

My views on the evolution of gender equality in hepatology and what would be the next steps allowing to reach it.

The gender disparity in academic and clinical is a highly debated topic worldwide, yet progress is still too slow. Indeed, currently, almost in all the countries, women are still underrepresented in academic leadership positions, journal authorship, and speaker invitations.

Analysing the situation of the scientific sector of Gastroenterology and Hepatology in Italy, we observe that whereas the number of assistant professor is very similar between men and women, the percentage of women continues to decline at the highest levels of the academic career (only 29% of associate professors are women, and only the 14% of full professor).

The reasons for sex inequity in medicine and the slower advancement of women in academic medicine are complex and influenced by multiple factors including cultural values, balancing family responsibilities with professional growth, gender bias in the promotion process itself or in the various steps required for promotion.

While we intuitively know that achieving gender equity is simply the right thing to do, the scale of the problem can sometimes feel overwhelming.

Managing implicit bias so that women in medicine are treated equitably begins at the organisational level, with institutions must make gender equity an essential part of their missions. Furthermore, in my opinion, it is very important that the problem of gender inequalities in medicine be brought to the attention of the public opinion, talk about it in the media, raise awareness among students and future doctors.

A very interesting initiative was undertaken in Italy, with the establishment of the Top Italian Women Scientists (TIWS) group, of which I am an active member. The group, established in May 2016 and chaired by Prof. Adriana Albini, creator of the initiative, brings together female excellences, women who are characterised by high scientific productivity and who have made a substantial contribution to development in the biomedical field, in clinical sciences and neuroscience. The goal is to promote women research and bring young people closer to this world.

Unfortunately, larger societal change eliminating gender bias is unlikely, at least in the short term, but I firmly believe that it can be achieved through a series of small steps made by individuals and institutions.

Nevertheless, on a more personal level, I must say that I have not had any negative experience in my career as a hepatologist, neither in the academic nor in the clinical field, and I hope that this could be encouraging for the young hepatologists.

Prof. Helena Cortez-Pinto

EASL EU Policy Councillor (2016–2019)

Vice President of UEG

Full Professor in Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Portugal

Hepatology has very important female role models. In fact, Sheila Sherlock has been one of the most prominent figures in Hepatology, and since then, a very significant number of women have made very meaningful contributions to the field.

However, concerning leading positions in Universities or Clinical Departments, women tend to reach fewer leading positions. This is due to several causes, some more modifiable than others.

One, is the status quo, where male tend to select other male for positions or boards, because they are more similar, or because it is more traditional; also, females are usually less aggressive, and in the effort of conciliating family and professional life, tend to abdicate from the effort of pursuing such positions. This has negative consequences, including the creation of a vicious cycle, where male tend to perpetuate in these positions and female have less visibility, consequently decreasing their effect as role models. Also, the gain obtained by the gender diversity in teams is something that can be missed, if the inequalities are not reduced.

Recent years, have in my opinion, witnessed a significant effort towards decreasing the imbalance, with initiatives from both male and female individuals. Societies, such as EASL and AASLD, developed important initiatives in this direction, such as dedicated committees or policy statements. One first important step, is to recognize that the problem exists, and rules are often needed to mitigate it.

The issue of gender quotas is very controversial, rejected as a concept by many, but I believe sometimes useful, at least as a starting point. The protection of maternity, and the possibility to create mechanisms that recognize that the timing of careers in women can be different, and that should come without loss, are fundamental.

I believe we are in the right track, but still a long way to go.

[Women abdicating from pursuing leading positions] have negative consequences, including the creation of a vicious cycle, where male tend to perpetuate in these positions and female have less visibility, consequently decreasing their effect as role models.

Recent years, have in my opinion, witnessed a significant effort towards decreasing the imbalance, with initiatives from both male and female individuals.

I believe we are in the right track, but still a long way to go.

Prof. Maria Reig

Current Scientific Committee Member

BCLC group

Liver Unit. Hospital Clínic of Barcelona

University of Barcelona

We need to promote, at all levels, excellence in science.

First, believing that gender equality in science is possible.

Then promoting the dialogue and specific actions needed to demonstrate that being of a different gender does not mean your skills are necessarily stronger or weaker.

In my view, we need to promote, at all levels, excellence in the sciences, among people who are adept at promoting both teamwork and communication, on top of their gender or geographical origins.

Prof. Saskia van Mil

Current Scientific Committee Member

Professor of Molecular and Translational Metabolism

University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands

In my view, a lot has already changed. It is widely recognised now that more (gender) diversity will strengthen the performance of teams.

The change to having more females at higher positions in hepatology, and science in general is, however, very slow. I think that unconscious gender bias is the most important issue holding us back, preventing us from quicker progress in this direction. This unconscious, systemic prejudice of choosing males over females for higher positions, is based on our unconscious ideal, a stereotype, of how a key leading scientist in hepatology should look and act.

I think the most effective way of changing this stereotypic view of a “leading hepatologist”, is to have enough women role models at those positions. In my career, I have experienced a few times that due to gender quota policies, and female talent awards, I have had an advantage over my equally qualified male colleagues.

Although I very much dislike that I was not judged on my scientific and leadership qualities alone, I also think that “conscious intervention” is needed to eliminate the “unconscious bias”. These strategies to empower female scientists will get us more role models at higher positions.

This, in the long run, will change our unconscious views of how a leading hepatologist should look. I therefore applaud the way EASL is tackling this, by striving to have at least 30–40% of female scientists in each committee and conference session.

This unconscious, systemic prejudice of choosing males over females for higher positions, is based on our unconscious ideal, a stereotype, of how a key leading scientist in hepatology should look and act.

I think that “conscious intervention” is needed to eliminate the “unconscious bias”.